Understanding Tsunamis: Safety, Causes, and Historical Insights

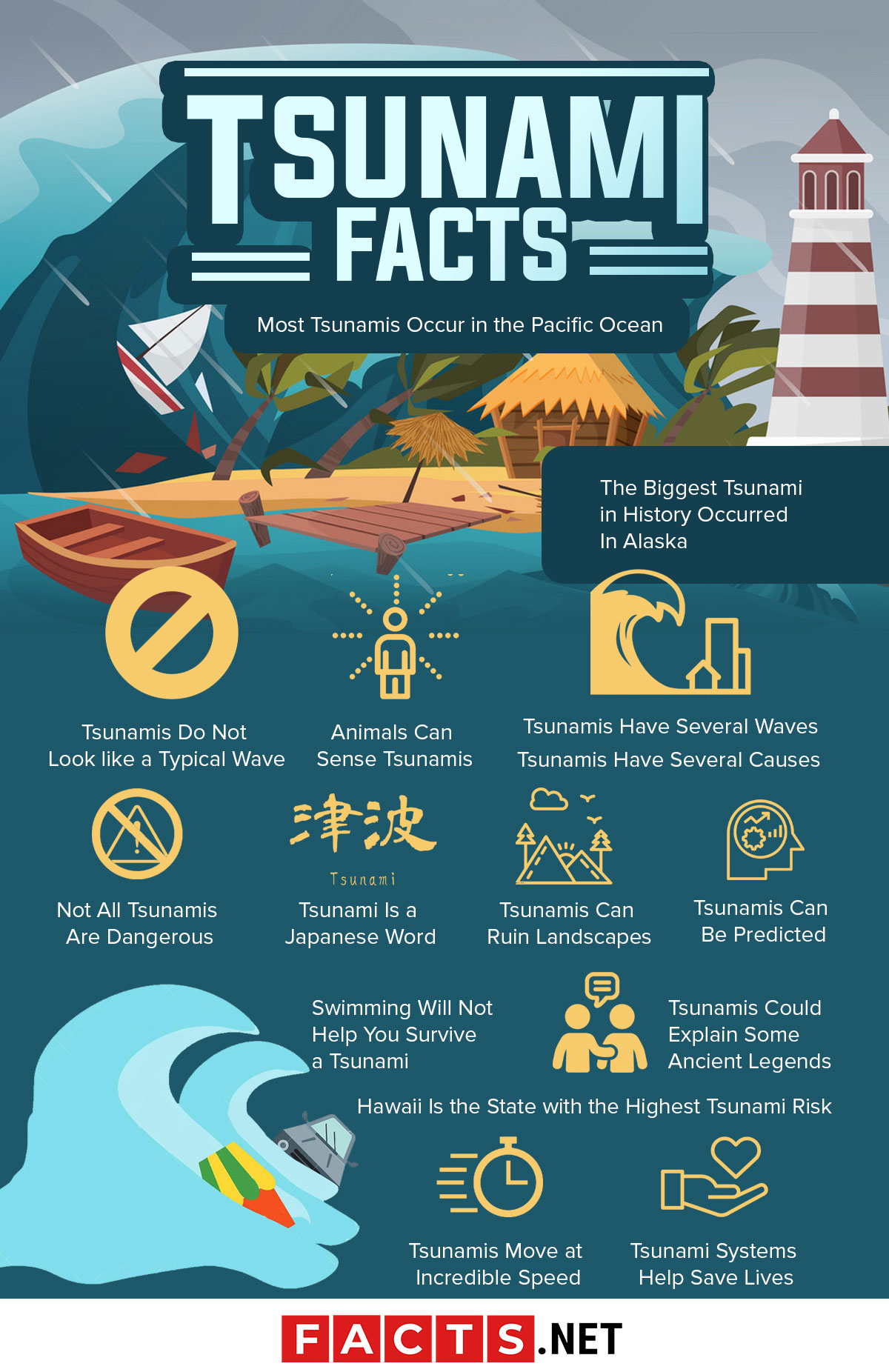

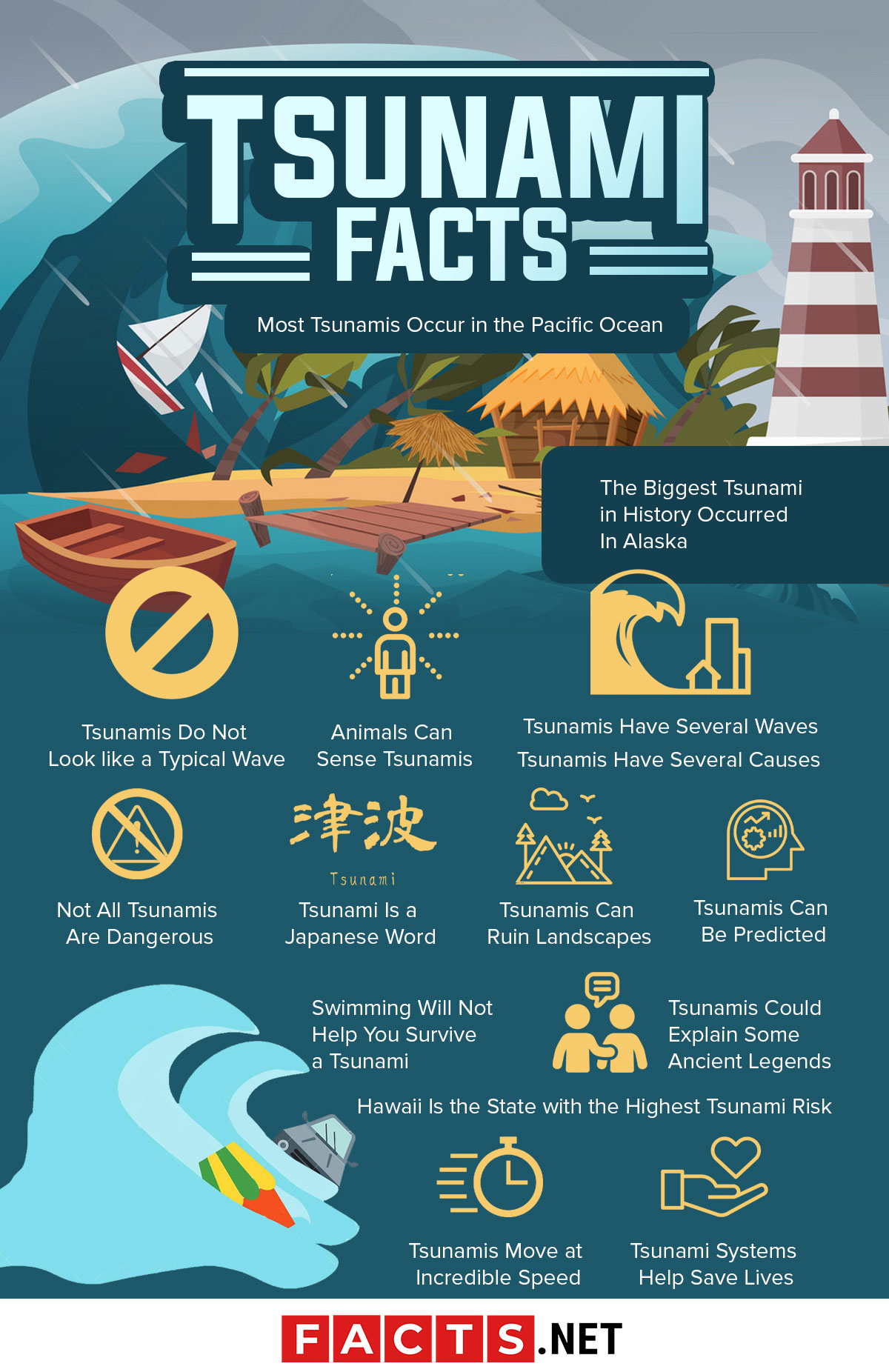

Tsunamis are powerful ocean waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, often due to underwater earthquakes or volcanic eruptions. Unlike regular ocean waves, which are generated by wind, tsunamis can travel across entire ocean basins and carry immense energy. They often appear as a rapidly rising tide rather than a breaking wave, making them particularly dangerous. The term “tsunami” comes from the Japanese word for “harbor wave,” reflecting their devastating impact on coastal areas. Understanding the nature and behavior of tsunamis is crucial for preparedness and response.

Historical Tsunami Events

Historically, tsunamis have caused substantial destruction and loss of life. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami is one of the deadliest natural disasters, claiming over 230,000 lives across 14 countries. This catastrophic event, triggered by a massive undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, illustrates the extensive reach and power of tsunamis. Japan, with its significant history of seismic activity, has also experienced devastating tsunamis, such as the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami. This disaster not only caused widespread devastation but also led to a nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. These events highlight the importance of understanding tsunami history for better preparedness. Tsunami records date back to ancient civilizations, with references from historians like Thucydides who connected tsunamis to submarine earthquakes. By studying past events, researchers can improve prediction models and enhance community safety measures. The historical context of tsunamis serves as a stark reminder of their potential for destruction and the need for ongoing vigilance.

Causes of Tsunamis

Tsunamis are primarily caused by seismic activities, including earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, and even meteorite impacts. The most common generators are tectonic earthquakes, especially those occurring at convergent plate boundaries. When the seafloor abruptly deforms, it displaces the overlying water, generating tsunami waves. This sudden movement of the Earth’s crust can release vast amounts of energy, resulting in waves that can travel hundreds of miles per hour across deep ocean waters. In addition to earthquakes, landslides can trigger tsunamis, particularly in lakes and coastal areas. For instance, a landslide into a body of water can create a wave that propagates outward, wreaking havoc on nearby shores. Volcanic eruptions—especially those that involve the collapse of a volcano—can also displace water and generate tsunamis. Understanding these causes is essential for effective monitoring and forecasting. Awareness of potential tsunami triggers can empower communities to implement early warning systems and better preparedness strategies.

How Tsunamis Propagate

Tsunamis propagate as a series of waves with very long wavelengths and low amplitudes in deep water, making them hard to detect. In the open ocean, tsunami waves can be spaced several hundred kilometers apart and travel at speeds comparable to a commercial jet, around 500 to 600 miles per hour. As they approach shallower coastal waters, their speed decreases while their height increases—a process known as wave shoaling. The wavelength shortens, and the wave can rise dramatically, sometimes exceeding heights of 30 feet upon reaching the shore. The dynamics of tsunami propagation depend significantly on the underwater topography and coastal features. Areas with abrupt changes in seafloor depth or narrow bays can amplify tsunami waves, leading to more significant impacts. Additionally, features such as islands or reefs can disrupt wave patterns, affecting how and where the energy is released. Knowing how these waves behave is crucial for coastal safety measures, as understanding their propagation can inform effective evacuation routes and disaster response plans.

Warning Signs and Preparedness

Recognizing the natural warning signs of an impending tsunami can save lives. Observing rapid sea level changes, such as a sudden retreat of water from the shore, can indicate the arrival of a tsunami. This phenomenon, often called “drawback,” occurs when the water is sucked back as the tsunami wave approaches, exposing the ocean floor. Local evacuation plans are vital, as it is often recommended to move to higher ground immediately after recognizing these signs. Tsunami warning systems, like those in Hawaii and the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, play a critical role in alerting communities. These systems utilize seismic data to detect potential tsunami-generating events and send alerts to those at risk. Emergency preparedness involves knowing evacuation routes and having a plan in place. Communities should conduct regular drills and educate residents about the signs of tsunamis to enhance readiness. By fostering a culture of preparedness, lives can be saved in the event of a tsunami.

The Impact of Tsunamis

Tsunamis can cause catastrophic damage to coastal communities, leading to significant loss of life and property. The force of the water, combined with debris, can create a deadly environment. Low-lying areas are particularly vulnerable to flooding, and the aftermath can disrupt utilities and infrastructure for extended periods. The economic impact of tsunamis can be profound, affecting local businesses and tourism, often taking years for communities to fully recover. In addition to immediate destruction, tsunamis can lead to long-term environmental consequences, including habitat destruction and changes to coastal ecosystems. The impact on human life and livelihoods underscores the importance of effective disaster response plans. Communities must prioritize resilience through infrastructure improvements and comprehensive recovery strategies. Understanding the potential impact of tsunamis emphasizes the need for proactive measures to safeguard lives and property.

Post-Tsunami Recovery and Lessons Learned

Recovery from a tsunami involves extensive efforts in search and rescue, rebuilding, and community support. Historical events have prompted improvements in tsunami forecasting and warning systems, leading to better preparedness. For instance, the devastating lessons learned from the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami have resulted in the establishment of more robust international warning systems and community education programs. Lessons learned from past tsunamis inform current safety protocols and infrastructure development. Community resilience and education are vital for reducing the risks associated with future events. Continuous evaluation of tsunami preparedness ensures better responses in the face of similar disasters. By learning from past experiences, communities can strengthen their defenses against future tsunamis, fostering a culture of awareness and preparedness.

Conclusion: Staying Informed and Prepared

Tsunamis remain a significant threat to coastal areas around the world. Staying informed about tsunami risks, understanding their causes, and recognizing warning signs are crucial for personal safety. Communities must prioritize preparedness through education, planning, and drills. As climate change and geological activity continue to evolve, ongoing research is essential for improving tsunami forecasting and mitigation strategies. Awareness and readiness can make a profound difference in saving lives during a tsunami event. By fostering a culture of preparedness and investing in community education, we can reduce the risks associated with tsunamis and enhance our resilience to future disasters. Understanding the science behind tsunamis and the importance of preparedness is essential for safeguarding our coastal communities.